Migration

in Detail - (Part 2)

In the previous

article in this series, we looked at one of the energy-saving

flight modifications used by ospreys and other raptors during their

migrations. Like human glider pilots, ospreys have developed a whole

range of techniques that can be used - either singly or in

combination – to gain maximum advantage from the prevailing

conditions.

Using data from the

latest GSM-type tracking units, which can log flight parameters at

intervals of minutes - rather than hours, as was typical of the older

UHF devices – we can get a much clearer view of what these birds

are doing and how they are doing it...

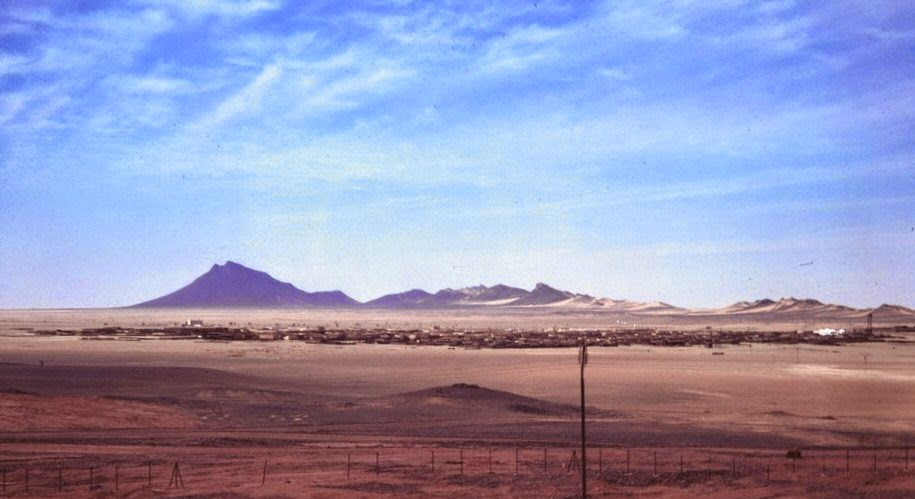

In November 2014, adult

male osprey “Tero” was flying south-west down the Arabian

Peninsula. After a major diversion to avoid adverse weather south of

Iraq, he had reached the Jabal Tuwayq - a long north-south

escarpment that marks the eastern boundary of the Asir

Highlands in Saudi Arabia. The winds were light but slightly against

him. But Tero was able to use the overall rising air current caused

by the gentle terrain gradient in a method known to pilots as “slope

soaring”

As with the “crosswind

tacking” technique, this allowed him to gain altitude by turning UP

the slope, and then maintain course progress by flying down it at a

shallower angle. The advantage of this system is that it works for

almost any wind direction that is at a greater angle to the line of

slope than 30 degrees.

As with the “crosswind

tacking” technique, this allowed him to gain altitude by turning UP

the slope, and then maintain course progress by flying down it at a

shallower angle. The advantage of this system is that it works for

almost any wind direction that is at a greater angle to the line of

slope than 30 degrees. |

| "Blue 7H" (Image: Joanna Dailey) |

A variant of this

flight mode is what I've chosen to call “ridge riding”. It is an

adaptation to more complex upland terrain where there are many

changes of elevation, with steep-sided river valleys and hill crests.

And the example chosen this time features “Blue 7H” - a female

first-time migrant from nest #2 at Kielder Forest. Blue 7H provides

the possible answer to a question that came up on one of the

discussion groups, which (in summary) was:

“Do juvenile birds have the innate (instinctive) ability to use these energy-saving techniques, or do they have to learn them as adults?”

“Do juvenile birds have the innate (instinctive) ability to use these energy-saving techniques, or do they have to learn them as adults?”

|

Only seven days after

leaving her natal nest, 7H had reached the Galicia region of

northwest Spain. Crossing this mountainous and forested landscape,

she took advantage of local up-currents along the windward side of

ridges to maintain the necessary height and made good progress

southward and into Portugal. It seems like even a young bird of prey

comes equipped with the full repertoire of flight, and only needs to

add a modicum of practice. This confirms visual observations of

other migratory species on their first migrations.

In the final part of this series, we will look at some other flight modes that are used by ospreys, and see how their anatomy and wing layout influences what they are able to do.

In the final part of this series, we will look at some other flight modes that are used by ospreys, and see how their anatomy and wing layout influences what they are able to do.

Wildlifewriter

acknowledges the use of tracking data supplied by the Natural History

Museum of Finland (Luonnontieteellinen

Keskusmuseo)and the Finnish Osprey Foundation, and data and images by Forestry

Commission England.

Links:

LUOMUS: http://www.luomus.fi/en

Kielder Osprey Blog: https://kielderospreys.wordpress.com/