Judging the onset of migration

“The time is out of joint—O cursèd

spite,

“The time is out of joint—O cursèd

spite,That ever I was born to set it right!

Nay, come, let's go together. “

Hamlet I,v

As we approach the end of January, it

might seem as if the time of Spring migration is still a long way off

– but in fact, things are already changing for our birds down in

Africa...

Long-distance migration is no trivial matter. A bird cannot just one day decide “It's probably time that I was heading back to my summer nest. Better get moving.” Before THAT happens, birds must make physical preparations and some of these preparations can take many weeks. In some species, feathers must have been moulted and new ones grown out. And in almost all species, substantial reserves of body fat have to be laid down as fuel for the coming journey.

And then there's the matter of timing.

|

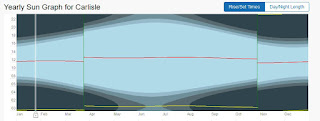

| "Sunpath" diagrams for 55ºN (left) and 15ºN (right) Click for larger |

It's been known for centuries that

migratory birds use changes in the length of day (“photoperiod”)

as one primary factor in knowing when to migrate. The biological

mechanisms of how this works are complicated, and links to further

reading are given below. We now know that animals have internal

“clocks” that keep track of time over various periods, from daily

rhythms to the cycle of the whole year. These timers are moderated

by external factors including photoperiod, changes in temperature,

and even (in some cases) location-specific alterations in the flux of

Earth's magnetic field.

|

| 5F in the Gambia [C. Wood] |

In west Africa, the ospreys are already

measuring changes in the day length and the accuracy with which they

have to do this is rather surprising.

Here in northern Europe, even we humans can notice that we have now passed the Winter solstice and the days are growing longer again.

At a latitude of 54.5ºN (where this author lives) each day is three minutes longer than the previous one (19th Jan 2017) and the rate of this change is increasing by about three to four seconds every day.

Here in northern Europe, even we humans can notice that we have now passed the Winter solstice and the days are growing longer again.

At a latitude of 54.5ºN (where this author lives) each day is three minutes longer than the previous one (19th Jan 2017) and the rate of this change is increasing by about three to four seconds every day.

This rate-of-change variable seems to

be very important to migratory birds. After all, some of them

(swallows, for example) are wintering south of the equator – where

the days are still getting shorter.

These changes are tracked by photoreceptors deep in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. The exact details of what happens during this process are not fully understood, but it appears that some kind of phase-comparison is being made between the amount of light being detected, and the “position” of the bird's internal circadian clock. We suspect this because if either mechanism is interfered with, the bird will no longer be able to evaluate photoperiod changes correctly.

These changes are tracked by photoreceptors deep in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. The exact details of what happens during this process are not fully understood, but it appears that some kind of phase-comparison is being made between the amount of light being detected, and the “position” of the bird's internal circadian clock. We suspect this because if either mechanism is interfered with, the bird will no longer be able to evaluate photoperiod changes correctly.

|

| Unringed osprey, Gambia [C.Wood] |

But, however it all works, the fact is that the faraway birds are already making their preparations to return for the coming summer.

I'm ready. Are you?

(Thanks to Chris Wood for the use of original photographs)

[1] Evans, P. R. “Timing Mechanisms

and the Physiology of Bird Migration.” Science Progress (1933-

), vol. 58, no. 230, 1970, pp. 263–275. www.jstor.org/stable/43419959.

[2] Ubuka T, Bentley GE, Tsutsui K.

Neuroendocrine regulation of gonadotropin secretion in seasonally

breeding birds. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2013;7:38.

doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00038.

[3] “Seasons of Life” L.Kreitzman, R. Foster: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Seasons-Life-biological-rhythms-survive-ebook/dp/B003ZDNWNQ/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1485272609&sr=1-1&keywords=9781847652799